There are those books you hear about for years that no one you know has ever actually read, but are generally accepted as classics of the genre. One of those in the world of organic agriculture is Franklin Hiram (FH) Kings’ Farmers of Forty Centuries.

It’s referenced over and over in permaculture and composting literature as a classic of composting. Published in 1911 by Carrie Baker King, FH King’s widow, the book is an account of FH King’s travels in China, Korea, and Japan for nine months in 1905. I expected a torporous tome of in stilted archaic language with painfully detailed and slow descriptions of things.

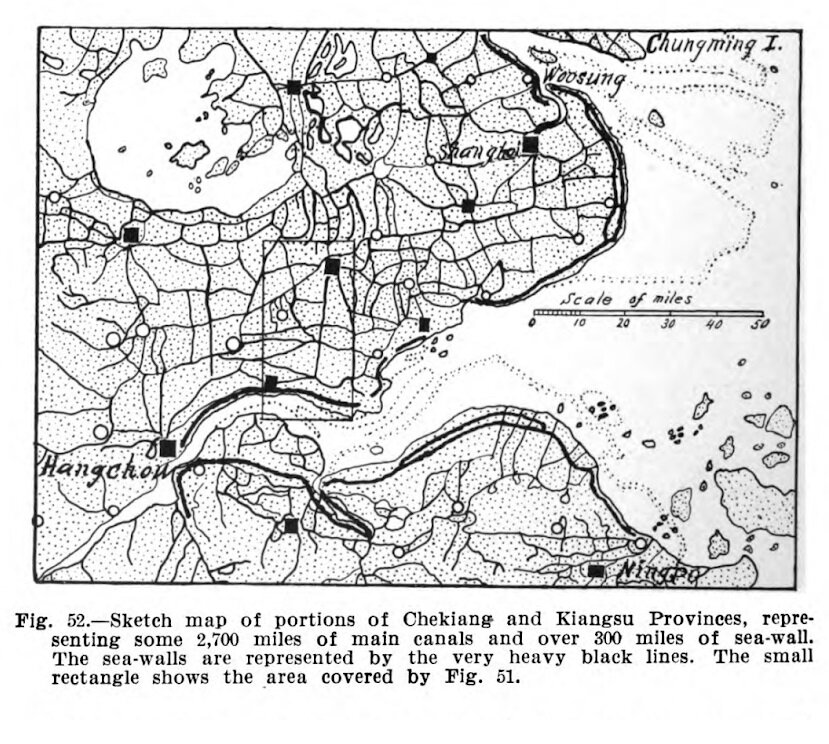

I was totally wrong. Professor King’s prose is compelling, deeply admiring of the people and cultures he encountered, and the 423-page book includes 248 photographs of surprisingly excellent quality. King describes his personal adventures in China - getting lost at night on a Rick-sha without an interpreter, paying for a stay on houseboat lived on by a family of eight and exploring China’s incredibly extensive canals.

And waxes philosophical on the comparatively wasteful farming of the United States, while himself quoting Booker T. Washington:

Man is the most extravagant accelerator of waste the world has ever endured. His withering blight has fallen upon every living thing within his reach, himself not excepted; and his besom of destruction in the uncontrolled hands of a generation has swept into the sea soil fertility which only centuries of life could accumulate, and yet this fertility is the substratum of all that is living.

…

The Mongolian races, with a population now approaching 500 million, occupying and area little more than one-half that of the United States, tilling less than 800,000 square miles of land, and much of this during twenty, thirty, or perhaps forty centuries; unable to avail themselves of mineral fertilizers, could not survive and tolerate such waste. Compelled to solve the problem of avoiding such wastes, and exercising the faculty which is characteristic of the race, they “cast down their buckets where they were” as,

A ship lost at sea for many days suddenly sighted a friendly vessel. From the mast of the unfortunate vessel was seen a signal, “Water, water; we die of thirst!” The answer from the friendly vessel at once came back, “Cast down your bucket where you are.” A second time the signal “Water, water; Send us water!” ran up from the distressed vessel, and was answered, “Cast down your bucket where you are.” And a third and fourth signal for water was answered, “Cast down your bucket where you are.” The captain of the distressed vessel, at last heeding the injunction, cast down his bucket, and it came up full of fresh sparkling water from the mouth of the Amazon River. - Booker T. Washington

Composting Methods

Of course, as a compost lover and maker, I’m fascinated by the methods described and ingredients used in compost making.

In various regions of China and Japan there were locally adapted methods of compost preparation. All of them seem extremely laborious, especially when considering that all of the materials were gathered and moved by hand, occasionally with the help of a beast of burden.

The two main methods I’ve been able to understand so far, are not at all like the aerobic composting I’m accustomed to. In the photo above, we see compost pits, where material (including human manure) was allowed to ferment anaerobically, under water and the silt/sludge, would be scooped out of these pits, or canals, with long handled cloth ladles and carried in baskets to the fields.

Underwater fermentation is suggested in the modern offshoot of Korean Natural Farming called JADAM, and the dipping and use of canal/pond muck is used extensively in the legendary chinampas of Mexico, which themselves are the heritage of the Aztec empire, and still in cultivation.

Many modern compost texts and teachers eschew anaerobic fermentation out of hand, rejecting it as a disgusting, inefficient, bad for soil health, and attractive to flies. Yet King notes the remarkable cleanliness and lack of flies around farms in China:

We have adverted to the very small number of flies observed anywhere in the course of our travel, but its significance we did not realize until near the end of our stay. Indeed, for some reason, flies were more in evidence during the first two days on the steamship, out of Yokohama on our return trip to America, than at any time before on our journey. It is to be expected that the eternal vigilance which seizes every waste, once it has become such, putting it in places of usefulness, must contribute much toward the destruction of breeding places, and it may these nations have been mindful of the wholesomeness of their practice and that many phases of the evolution of their waste disposal system have been dictated by and held fast to through a clear conception of sanitary needs.

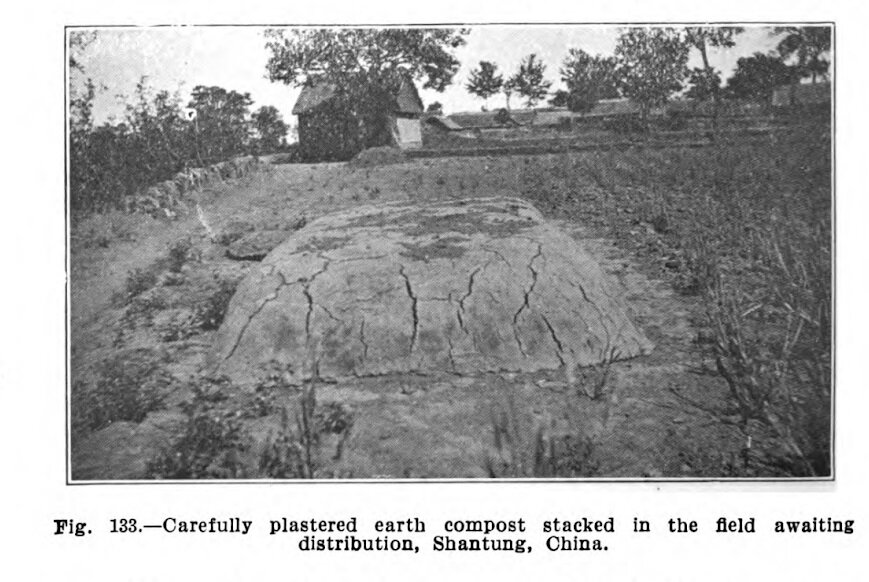

In some cases, the anaerobically fermented material would be pulled out of the compost pits and mixed with soil and made into blocks and turned regularly, further allowing fermentation and making available the nutrients in the compost materials. Why so much effort went into homogenizing and pulverizing the material is not clear to me, but was clearly important to these Chinese farmers.

The fullest description of how these compost piles were composed (that I’ve read yet, I’m on page 298 currently) follows:

The compost pit in front of where we sat was two−thirds filled. In it had been placed all of the manure and waste of the household and street, all stubble and waste roughage from the field, all ashes not to be applied directly and some of the soil stacked in the street. Sufficient water was added at intervals to keep the contents completely saturated and nearly submerged, the object being to control the character of fermentation taking place.

The capacity of these compost pits is determined by the amount of land served, and the period of composting is made as long as possible, the aim being to have the fiber of all organic material completely broken down, the result being a product of the consistency of mortar.

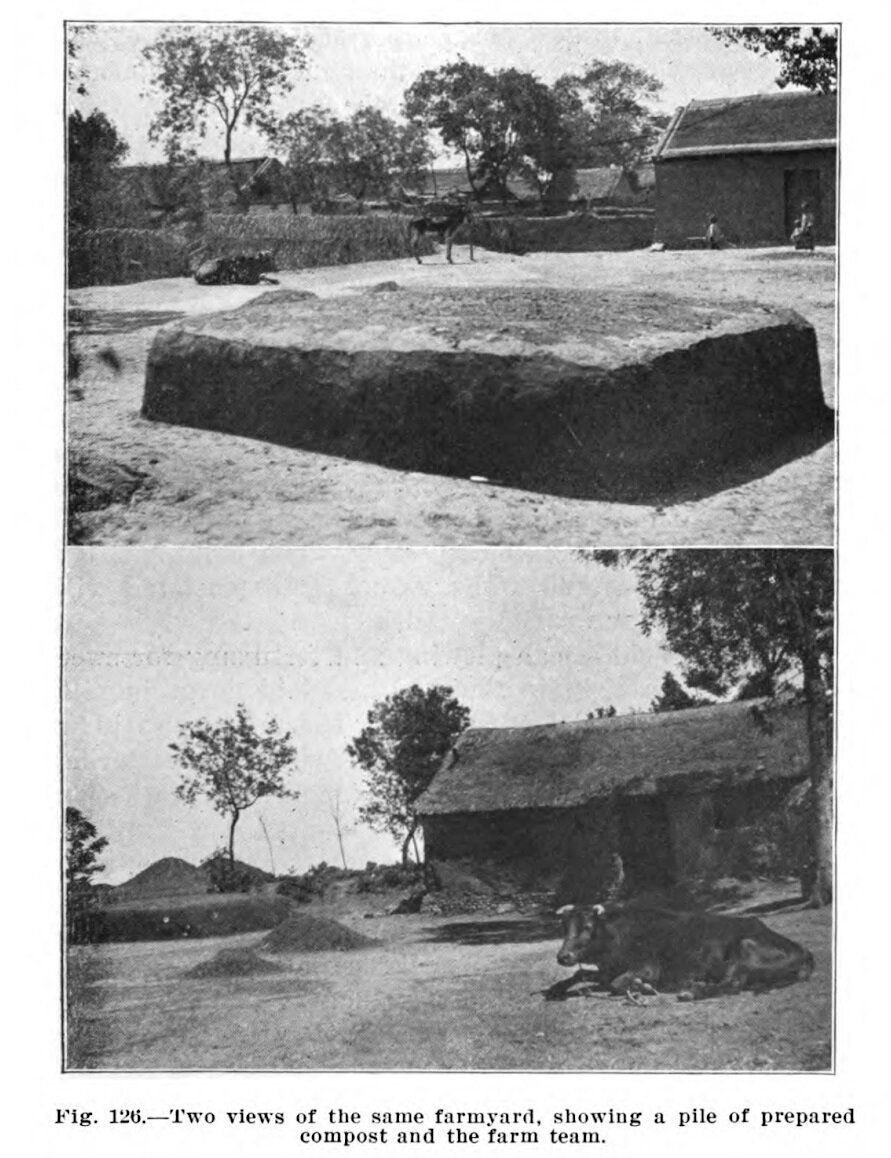

When it is near the time for applying the compost to the field, or of feeding it to the crop, the fermented product is removed in waterproof carrying baskets to the floor of the court, to the yard, such as seen in Fig. 126, or to thestreet, where it is spread to dry, to be mixed with fresh soil, more ashes, and repeatedly turned and stirred to bring about complete aeration and to hasten the processes of nitrification. During all of these treatments, whether in the compost pit or on the nitrification floor, the fermenting organic matter in contact with the soil is converting plant food elements into soluble plant food substances in the form of potassium, calcium and magnesium nitrates and soluble phosphates of one or another form, perhaps of the same bases and possibly others of organic type. If there is time and favorable temperature and moisture conditions for these fermentations to take place in the soil of the field before the crop will need it, the compost may be carried direct from the pit to the field and spread broadcast,to be plowed under. Otherwise the material is worked and reworked, with more water added if necessary, until it becomes a rich complete fertilizer, allowed to become dry and then finely pulverized, sometimes using stone rollers drawn over it by cattle, the donkey or by hand. The large numbers of stacks of compost seen in the fields between Tsingtao and Tsinan were of this type and thus laboriously prepared in the villages and then transported to the fields, stacked and plastered to be ready for use at next planting.

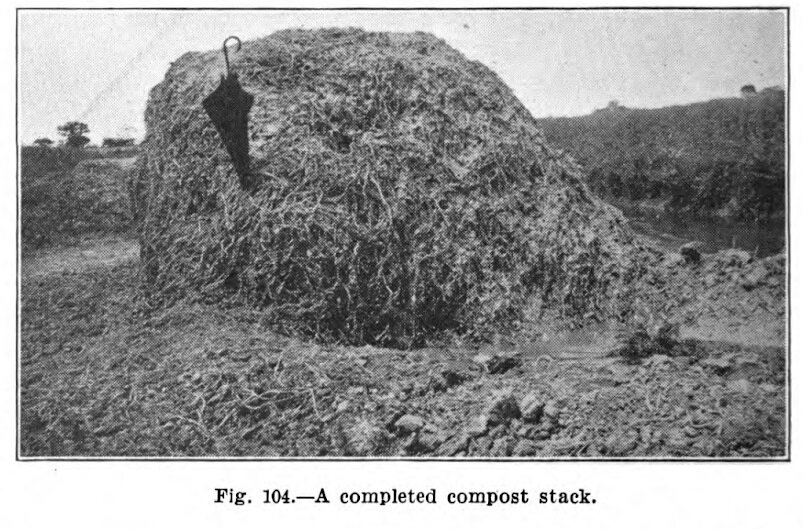

The other method similarly involves fermented canal or compost pit muck mixed with green plant material. Below is an image of a compost stack that was built layer by layer of cut clover covered with compost muck, and stamped on by foot, until it grew to this height, with F H King’s umbrella on the stack for reference. This is then let to ferment for about half a year before being applied to the fields.

Reflections

I’m struck by the incredible work put into preparing composts and fields described and am amazed at how these methods developed over time in a peasant-subsistence society.

King was famous also for his text on agricultural physics, and his knowledge of soil chemistry - but an understanding of soil biology hadn’t happened yet. (That would wait for Annie France Harrar of Germany and Nikolai Aleksandrovich Krasil'nikov of Russia in the middle of the 20th century). And King’s view of agriculture was essentially extractive - that is, that plants pull nutrients out of soil and those nutrients must be replaced every year in order to maintain the health and fertility of the soil.

In 1975, the now-famous natural farmer Masanobu Fukuoka reacted against this sort of traditional east Asian agriculture and extractive mindset in One-Straw Revolution. There he inveighs against the unnecessary labor of making all of these extensively prepared composts and natural fertilizers, and the view of nature in parts, rather than an indistinguishable whole.

That said, FH King’s work stands the test of time and is absolutely worth your time.

by: Nathan Rutz